.

“Birth is not merely that which divides women from men: it also divides women from themselves, so that a woman's understanding of what it is to exist is profoundly changed.”

- Rachel Cusk

.

Like many new moms who suffer from extreme anxiety, I am prone to reading.

I read books.

I read articles.

I read product reviews.

I read the bios of the reviewers writing the reviews.

And, through my reading, I learn.

As a new mom, I have learned co-sleeping is dangerous. I have learned how a baby’s sight changes with each passing day. I have learned high-contrast objects help newborns—in particular—to focus, that initial playthings should be black and white and red.

I have learned I can (if I want) attach balloons to my own baby’s appendages to help her understand cause and effect, her tiny hands and feet tugging on tinsel. I have learned this is something I decide I want to try.

I have also learned that in the the first three months of life, a baby does noes not realize they are a separate person from its mother. My baby, while she stares mesmerized by spinning ceiling fans in our living room or smiles at strings of twinkle lights on the fences in Old Town Key West, does not know her long, tapered fingers she folds over her face like the Mouse King in the Nutcracker or her excessively chubby feet that resemble pillows are hers, nor does she understand the heartbeat reverberating under her chin as I write this is now.

It has been no surprise to me that in the first few months of parenting, the eat/change/feed/sleep demands of motherhood makes so many women feel a physical loss. On top of the continued extraction of nutrients from mother’s bodies (iron from blood, calcium from bones) and unending distortion of the maternal figure—the re-rounding of tummies, kneading of thighs, taffying of jowls, mothers are effectively “one” with their baby.

It has also been no surprise that with the baby's constant demands and oppressive presence, there is another, metaphorical loss of self. The person the woman once was now vulnerable to self-erasure, self-puncturing, fading, deflation, disappearance.

What has surprised to me: I feel but mourn neither loss.

Perhaps I can attribute this to the books like Rachel Cusks' A Life's Work and Lucy Jones’ Matrescence I read (and read and read) in fear of what postpartum dared bring or to my weekly Instagram surveys to old and new moms alike or to my following of many “momfluencers” who religiously share their families and their homes and their routines and their tears in videos overlayed with poppy music and glowing with premium Edge-Lit technology. Or, maybe, I owe this to the chronic illness I have had for nearly 10 years. The one that asked me to say many goodbyes to the many selves I knew—both carnal and symbolic.

What I don’t hear talked enough about are mothers mourning their future selves. Not future homes and vacations and monetary gain but actual selves. I mourn this other unknown person, this afternow human—the woman-writer I was working for—or toward, had hope for and hoped for. And, I mourn the world in which she would have lived. A world in which she would no longer use air quotes when asked what she did or who she was or what made her her. (Read: “writer.”)

I’ve asked: Is this mourning justified?

And, I think it is.

In part.

In literature, mothers postured as mothers rarely have “main character energy” and thus rarely serve as main characters. Motherhood—in its ubiquitousness—seems to have been earmarked as cliched. We are told a mother is a mother is a mother, and her duties abound but these duties are banal, her very being: a platitude. For the mother, there is one focus, one track: her children. For the mother, beyond birth, no climax exists. She is of one locality, a stable player—or else oscillating frantically but never heroically between mothering and mother-guilt. She is small in her actions—washing, cleaning, cooking, or working only to return home to wash, cook, clean, and is as much a fixture as the things in her house: the diapers and the pots and the pans, her baby's spit-up blankets, bottles, and pump parts. She is somehow a setting from which other—more prominent—actors spring.

Freud claimed by the time a woman is thirty her psyche "has taken up its final positions, and...there are no paths open to her for further development” and suggested that for mothers, their story is over. In the world of literature, too, it seems to me that for mothers wanting to write to their life, the road no longer diverges. The road ends. (For what famous poems about motherhood do people post, what books detailing a mother’s life prevail?)

The scarcity of mothers writing openly about mothering makes me believe that my time as a woman-writer writing about self is over—in some ways because self is over, but also because I have reached an agreed-upon end state. Unable to try on new and different selves, I am immutable. Static in my post-frump body and mind and experience.

A few months before I was to give birth, frumpy and swollen and fearing what the “post” in postpartum could hold, I exchanged texts with a friend about her own postpartum experience, the baby blues, and PPD. As we wrote, she used the word "despondent" to describe how she felt during a particularly difficult period.

A few months later, once my baby, Aoife, was born, the word cropped again. A mentor had written, and I wrote back, expressing my disappointment—in my writing and also to be seen by someone who can write and deserves to write in the world (a feeling perhaps birthed from the perceived narrative—or lack of narrative—of mother-writers in the world).

Etymologically, the word despondency comes from the Latin despondere—de meaning “away” and spondere meaning “to promise.”

My friend used the word as a way to describe distance from excitement, far-ness, gone-ness, away-ness from self as self should be. She used the word in a way that made despondency feel like a wisp of self, or—maybe more apt, a hologram glitching in and out of oblivion. In my exchange with my mentor the word came to underline discouragement and disappointment. A detraction of hope, a detesting of self and situation. A friction—between actuality and expectation, and maybe only one that is but temporary.

A new mom, I am now familiar—even intimate—with despondency, but for me, it has been less a feeling arising from an erasure of self or a momentary disappointment in reality, but a deep, deep fear of what will never be.

Writer. “Writer.” Writer. I have tried on the office for nine years and have been hesitant to call myself such for all nine years, though a writer I am. I write line upon line, shape poem after poem—some of which have found homes, many of which have not. In front of me: a document titled NewPoems.docx with over 300 pages. Behind me: a train of rejections. And, more recently, wiggling its groove into view: a kind of line in the sand.

As the birth of Aoife neared in August and September of this year, I imagined this figurative line growing, and rejections from journals and presses were felt as acutely as never before. The templated emails politely turning down my work with the word “unfortunately”—which once would have prompted a quick and unblinking ‘delete’—reminded me with a sting that I had so little of this big part of my life to show my daughter. The emails felt not like small gates closing but that the biggest gate was coming to pass.

Soon after Aoife’s birth, I found myself in a local coffee shop eating pumpkin seeds off a sweet loaf, stumbling through Milkweed Smithereens—Bernadette Mayer's final collection, and seeing my future self not singularly but in split screen: one self refusing to give up aspiration and one self mourning a life unknown.

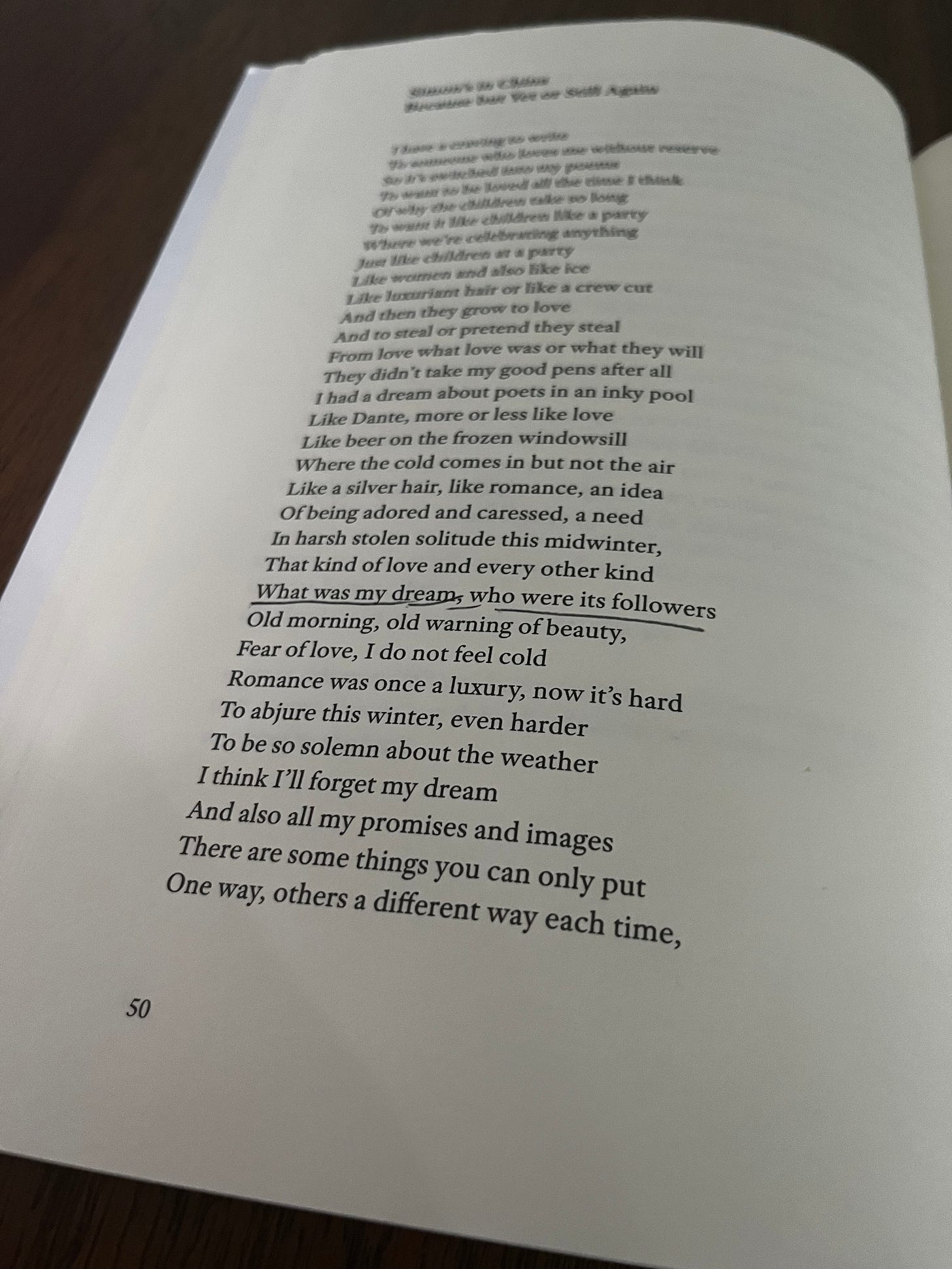

Milkweed Smithereens is disorienting in its temporality, in its form, and in its movement between politics and nature, and people, and I found this coda from Bernadette (a mother of three who wrote a book in one day) at times a difficult stream to follow. At others, I found in the verse odd rocks on which I could—in my own postpartum disorientation— sit, or even stand. The nonsensical making a kind of sense:

“can you feel sorry for a field?”

“it was june 10, cloudy & windy, a tree”

”i dreamt i was a pinnacle of coral”

“so many leaves are

falling, it’s exhausting”

It was in the poem “Simon’s in China/Because but Yet or Still Again” that I found a stone echoing the stone from which I worried I might slip. This one line making me come apart in selves and cry over an overpriced, oversugared latte:

“What was my dream, who were its followers.”

What was my dream…

Who were its followers…

In the following lines, the speaker is decided—it is too hard (the “winter,” the “weather”—life). She thinks she will “forget the dream,” and “all [her] promises and images.” Like the speaker, I thought in that moment I could possibly (maybe, at least try) to forget the dream, but unlike the speaker I kept looping back to the dream or the thought of the dream and then the loss of it—pulled in like a wave of sureness then sent out in a forgetting. In and out, in and then out, remembering what was then forgetting what is, remembering the dream again.

And, so, friends(?), readers(?), maybe just this great big vacuum into which I jot, scribble—make sense: what is this piece of materiality—this newsletter and its intent? A kind of writing and therefore a kind of dream. Or, a continuation of a dream. Or, maybe just a making sure—through the thick of motherhood—I can still remember what it feels like to be in my dreaming.

Welcome.